As defined by the Encyclopedia Britannica, a wildcat strike is a "strike action taken by workers without union authorization, in defiance of accepted union procedures." Based on an expert opinion by Hans Carl Nipperdey, a former Nazi lawyer who later presided over the Federal Labor Court, wildcat strikes are not legal in Germany. Hereafter, work stoppages can only and exclusively be organized in connection with collective bargaining and only at the request of the unions.

A Brief History of Migrant Wildcat Strikes in Germany

Nonetheless, several wildcat strikes ornament German post-war history, each opening the door for the next one wider. One of the most famous is the Ford Strike of 1973 initiated by the so-called 'guest workers'. Thousands of migrant Ford workers in Cologne demanded better working conditions, higher wages, and enhanced workers’ rights from the country they were rebuilding after World War II. Basically, as ‘guests’, they were demanding just a small gesture of hospitality. The strike started after a mass firing, getting media attention on the very next day – although not in a very positive way – and being seized by the police force within a week. Baha Targün, the person who initiated the strike, was exiled.

Among many others, another impactful wildcat strike initiated by migrant workers took place when workers of Pierburg, most of whom were women, articulated their demand for better working conditions and equal wages. The strikes faced strong opposition from the authorities, with the police often using force. However, a sense of unity emerged. Initially, on August 13, only a few workers took part in the strikes. Yet, as more workers were arrested and the management tried to intimidate them, more employees joined in. Eventually, the company had to respond. They increased everyone's wages by 30 Pfennig. This wildcat strike not only showed the power of solidarity but also boldly confronted the prevailing sexist norms of its era.

Time Loop Tangles: From Guest Worker to Wildcat Strikes in the Gig Economy

Almost fifty years after the decade of wildcat strikes against exploitation and racist labour practices in Germany, there is a new generation of precarious workers, I am part of. In 2021, during the Corona pandemic, when I started to work at Gorillas, a Berlin-based grocery delivery startup, in the first two weeks I was super happy as a part-time delivery rider. Because I was making more than what I would make as a full-time teacher at a prestigious school in my hometown in Turkey. But quickly my first impression changed. Many of us have come to avoid the oppression in our home countries. Every rider in this company has their studies but they cannot find proper jobs because they don't know German or their diplomas aren't recognized. In the gig economy, this precarity is being turned into a profitable business model.

Let me quote just a few of my colleagues and the experiences they made:

-

“We have six orders in one backpack, and that happens over and over again. Sometimes you can’t even close the ‘rucksack’ because it’s overloaded, and you still have to deliver everything. I have no idea how heavy the backpack is sometimes, maybe 40 kilos. You can hardly get it on your back. And that’s what it’s like for the whole shift for 8 hours.”

-

“In some of the warehouses, people experienced sexual harassment and racial discrimination, and we cannot openly get against them because most of us are on probation, which means that we can get fired without a reason.”

-

“Very often, workers ride their bicycles and, for example, the seat falls off or something breaks, which leads to accidents. Accidents are very common at this company. That also has to do with the company’s business model, which promises to deliver within 10 minutes. There have been very serious accidents – people with broken limbs, people who needed surgery. There was even a rider who almost died.”

Often those that were the most vulnerable or did not know their rights were the ones that were taken advantage of the most. At Gorillas, we as workers took a stand against these precarious working conditions in several ways, the most outstanding one being a chain of wildcat strikes we orchestrated. Let’s have a closer look at this case, because although the problems of Gorillas workers were similar to those of our strike-wise grandparents, the wave of strikes, blockades and protests lasted for months and there was luckily no police violence involved. But why do we say that the problems show similarity to those of fifty years ago, and although there was a decade of strikes, why does Germany still continue to fail its migrant workers after fifty years?

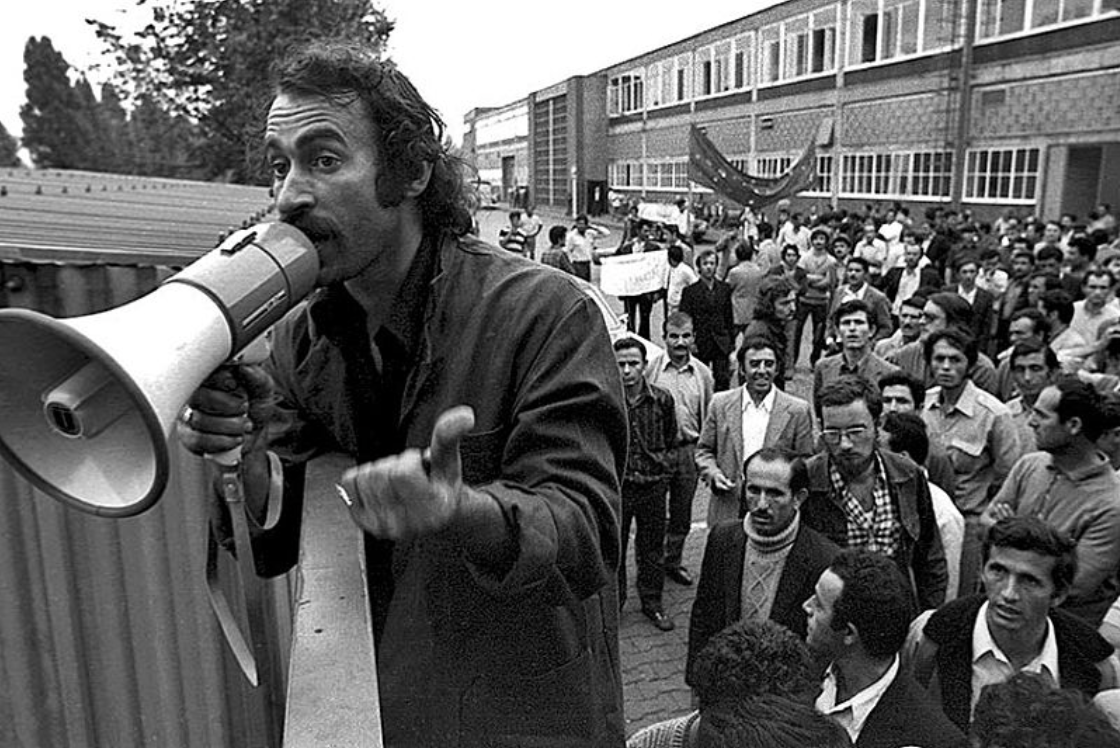

A demonstration organized by the Gorillas Workers Collective (Photo: Franziska Rau)

In Germany, there is a system where both works’ councils and trade unions play a role in influencing labour policies. In theory, all workers, regardless of where they come from, have the right to join either of these groups for representation. However, in reality, not all workers can go on strike or even get their concerns heard by works’ councils and trade unions. The problem is that there are old laws still in place designed to regulate guest workers, which restrict workers' ability to move around and get involved in workplace democracy and politics. That’s why the same tale from fifty years ago is retold today, but thanks to the struggles of the wildcat strike pioneers of the guestworker generation and the existence of modern social media, this tale has been adapted to these times.

Here is a brief retrospective of what happened when we realized that the Gorillas business model cannot work without us and how we as workers went on strike, kept the momentum for months, and are still on the way to changing regulations in Germany.

A group of workers, what we later called the ‘Gorillas Workers Collective’ (GWC), was formed, inspired by a group of workers refusing to work in subzero temperatures, thus leading to a week-long shutdown across all warehouses at Gorillas in February 2021. We were already trying to inform other colleagues about their legal rights, by organizing social gatherings, writing articles, and translating those information. When a co-worker publicly shared information about worker’s rights, it led to their dismissal without a warning because the worker was on probation. However, the company made a mistake in the termination letter. The worker had two options, they were either going to accept the dismissal or object to the mistake. In case the company received the objection, the company would correct the mistake in a few days and the worker would be dismissed again. Thus, whatever was to be done, had to be done in those few days. This led to Gorillas workers’ deciding to initiate a workers’ council process as a strategy to protect their colleague from this legal and moral scandal and to strengthen the organizing drive we were articulating.

According to German labour law, if a worker is part of a works’ council process by being an inviter, electoral council member, or workers’ council member, they are automatically out of probation, meaning that they enjoy special protection. The dismissed worker became one of the initiators of the process and thus couldn’t be fired without a warning.

In the case of Gorillas workers, forming a works’ council was not a problem language-wise, differently from fifty years ago. However, a works’ council, contrary to what many politicians and union representatives say, did not solve the ongoing problems as Gorillas refused to cooperate. Nonetheless, the GWC became popular among our colleagues as this formation revealed the problems at Gorillas, and the platform economy in general, by reminding workers that a dedicated group of workers is committed to actively contribute to address the company's failures.