What would it mean for work to be democratic?

Many of us spend large parts of our waking hours doing it, and many of us spend large parts of our waking hours looking for it when we don’t have it. But if this thing called work concerns so many of us, what would it mean to democratize it? Perhaps it should mean at least five things:

- High standards of rights for all workers, which ensure their equality, their dignity, their mental and physical wellbeing and their fair share of the benefits and profits their work contributes to, even if those benefits are not directly produced by the work itself (for example, teachers and cleaners clearly contribute to massive benefits for society, but don’t get paid in anything like an equitable way. It often seems like the more essential the work is, the worse it is paid!)

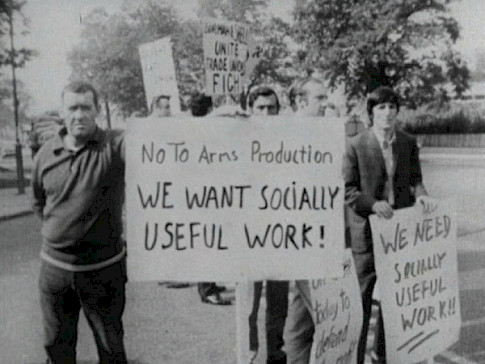

- Strong and inclusive worker organisations which enable workers to collectively protect, access and advance their rights vis à vis their employers, and also vis à vis the government. These worker organisations should be present in all parts of the economy, and provide collective agency to every kind of worker. This both implies it needs to be easy to set up worker organisations and that such organisations need to be open and non-exclusive.

- Recognising unpaid work as work: this includes care work, reproductive work, civic education, volunteering and other forms. These forms of work should be recognized as work, and society should ensure rights and recompense for this work, without subjecting them to market norms.

- Enough meaningful work for all: some members of society are overwhelmed with forms of paid and unpaid work, and others do not have enough. A democratic culture of work would seek to spread the load, spread the opportunities and spread the gains more equally.

- A model of governance for companies which gives meaningful voice over the business not only to employees but to all stakeholders, including citizens, local community and future generations, and models of accounting and audit which measure social and environmental impact.

Framing the struggle for better working lives as a struggle for democracy has a certain number of advantages. Above all, it emphasizes that we don’t stop being citizens with political opinions, interests, rights and divisions once we start the working day – politics reaches into our activity of labour. As workers we have a political agency, which we have to use deliberately and mindfully. Furthermore, as workers in a company we might easily be in regular contact with people who live in different places to us: the supplier in China, the designer in Chile, the accountant in the Czech Republic. Democratising work also means thinking about the democratic rights of these others in other places, in a way that thinking about democracy in our own countries through other activities like voting might not. And talking about democratizing work also encourages us to think about people who are not working: it is not just about democratizing the workplace, or democratizing companies; in our understanding of democratizing work we approach work holistically, thinking about how different kinds of work build upon and depend upon each other, and about how people affected by our labour can be given meaningful voice and even decision over it.