There is no capital that is a universal abstraction. Capital is always a practive, a determinate set of social relations and a cultural one at that. Thus ‘race’, gender, and patriarchy are inseparable from class, as any social organization rests on inter-subjective relations of bodies and minds marked with socially constructed difference on the terrain of private property and capital. [1]

»Why Intersectional Organizing Matters« – Some Lessons Learnt for Political Futures from the Margins

In the past couple of years, the question of how to build resilient social movements has largely shifted towards a discussion on how to secure and endure resistance in the face of climate destruction, fortress capitalism and war. As if we were looking through a magnifying lens, we see how the consequences of the dire condition of our planet and the return of authoritarianism and fascism do not affect us all equally. Instead, dynamics that may not be limited to class, race, gender, sexuality, or location position us differently in the face of our common vulnerability and precariousness coming from the exploitation, marginalization, and oppression we experience.

Women and queer Black and People of Color in the working classes of the global South are certainly among those groups who likely experience the effects of the ongoing destruction of our homes, bodies and resources in quite a different manner and proximity than many members of exploited and oppressed communities in the global north. This does not call for a valorization of struggles. Rather, it stresses the importance of making intersectionality a vantage point for the development of joint struggles, based on solidarity and kinship. We need to rethink the frameworks in which we both theorize and organize social movement building and community organizing in a way that accounts to the lived intersectional realities of people.

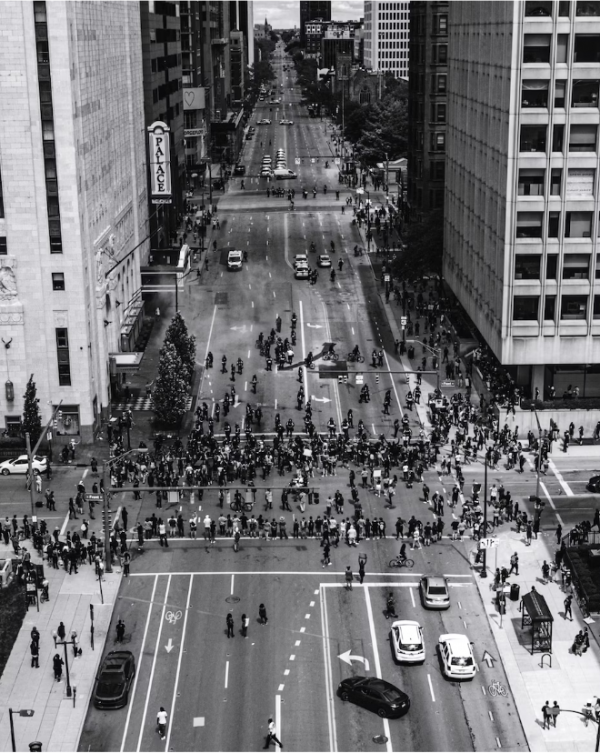

Black Lives Matter Protest (Photo: Mike Von & Tito Texidor III)

What “Intersectional Organizing” Can Be

In short, intersectional organizing may be understood as an essential process of decentering collective struggles. Instead of hoping for an eruptive revolutionary momentum that mobilizes the masses in the face of our joint issues, we shift our focus towards empowering marginalized communities and building networks of solidarity in difference. In intersectional organizing, we reject a politics of the 'lowest common denominator' in favor of a critical praxis that thinks collective struggles based on a radical appreciation of difference.

My lessons learnt lead to showing how a decentering of struggles that regards community building as a radical act may serve as an entry point to a conversation on a new politics of collectivity in the face of all-encompassing oppression. I extensively draw on Black feminist thought, which we owe most, if not all, of the contributions to progressive thought that connects to questions of community organizing.

As a metaphor for the complexity of Black women’s experiences of exploitation and discrimination, in the 1980s, Kimberlé Crenshaw introduced the term »intersectionality«. Building on Black feminist thought, intersectionality became an appealing figure to stress the multidimensionality of the experiences of Black women in the visual metaphor of a traffic intersection:

Consider an analogy to traffic in an intersection, coming and going in all four directions. Discrimination, like traffic through an intersection, may flow in one direction, and it may flow in another. If an accident happens in an intersection, it can be caused by cars traveling from any number of directions and, sometimes, from all of them. Similarly, if a Black woman is harmed because she is in the intersection, her injury could result from sex discrimination or race discrimination. [2]

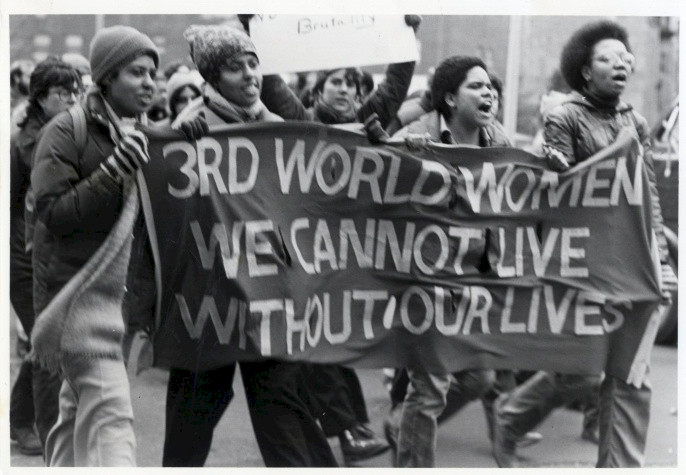

Anti-Racist Street Protest (Photo: Cyrus Gomez)

However, Black feminist struggles have been drawing on intersectional analysis in radical fashion even before the introduction and popularization of the metaphor. The Combahee River Collective, a group of socialist Black feminists, argued in a statement in 1983, that they came together as a group to articulate a specific perspective, a new form of identity politics, that centers their experiences as Black women and feminists, without detaching their specific struggle from that of Black men in a joint venture to tackle the issue of racism in the U.S., as well as class-oriented socialist politics. Contrary to the contemporary debate around the term ‘identity politics’, which has unfortunately become almost synonymous with political separatism, the Combahee River Collective sharply criticized the separationism of the predominantly white lesbian feminist movement of their times. In stating that “the liberation of all oppressed peoples [which] necessitates the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy” [3] must be the goal of all political struggles, the collective clearly positioned itself as part of an all-encompassing emancipatory struggle. However, they stressed that

We need to articulate the real class situation of persons who are not merely raceless, sexless workers, but for whom racial and sexual oppression are significant determinants in their working/economic lives. [4]

The Combahee River Collective (Photo: Unknown)

Based on the experience that neither Black and Brown men nor the white feminist or the socialist movement adequately addressed the situation of Black lesbian women, but rather themselves reproduced forms of oppression against them, they called for politics based within their own experience. They argued:

We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else's oppression. In the case of Black women this is a particularly repugnant, dangerous, threatening, and therefore revolutionary concept because it is obvious from looking at all the political movements that have preceded us that anyone is more worthy of liberation than ourselves. We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough. [5]

Based on such a complex political positionality, the Combahee River Collective developed numerous skilled activities for organizing within their community and beyond. Amongst those were workplace organizing, hospital picketing for adequate health care, organizing different types of welfare as well as daycare programs including a rape crisis center within a Black neighborhood.

Community Organizing: From Divide and Conquer to Divine and Nurture

The approach and the concrete politics that resulted from it, fit well some of the discussions we are having now around the question of ‘community organizing’. Before turning to that question, however, I want to draw the attention towards the practical political implications of an identity-based approach as it is proposed in the radical statement by the Combahee River Collective. How can we think collective political struggles from the multiple perspectives of oppressed realities and identities; from the plural points of views that come from the margins of societies?

In her article “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” (1983) the Black lesbian feminist poet Audre Lorde developed a perspective that radically centers difference as a source for collective struggles:

For difference must be not merely tolerated, but seen as a fund of necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic. Only then does the necessity for interdependency become unthreatening. Only within that interdependency of different strengths, acknowledged and equal, can the power to seek new ways to actively ‘be’ in the world generate, as well as the courage and sustenance to act where there are no charters. [6]

She argued that change can only be done in an acknowledgement of interdependence and community as central sources for collective struggle on the one hand, and the radical appreciation of mutual difference as a basis for collectivity on the other hand. Thought this way, change becomes a result of collective efforts that are not based on mutual experience, but on difference and shared support that is both solidarity in action as well as interdependency. It is precisely here, where radical Black feminist thought connects to the question of community organizing. With Marshall Ganz, community organizing is essentially the process of building relationships:

Organizers interweave relationships, understanding and action so that each contributes to the other. One result is new networks of relationships wide and deep enough to provide a foundation for a new community in action. Another result is a new story about who this community is, where it has been, where it is going –and how it will get there. A third result is action as the community mobilizes and deploys its resources on behalf of its interests – as services or as advocacy. [7]

Taking relationship building seriously and making it the vantage point of mobilization shifts the idea of mobilizing from mass protest towards building sustainable and resilient communities that can address and challenge the means of their exploitation and oppression through empowered self-articulation and self-organization that allows for care and solidarity in difference. A contemporary approach to social movement building – and theorizing – must therefore be rooted in connecting local rationalities based on a common understanding and acknowledgement of the particularities of each other’s struggles. [8] Community organizing becomes a radical act and a determinant for resilient social movements in the face of all-encompassing racist/colonial heteropatriarchal capitalism. Intersectional organizing may now be understood as an effort of self-empowerment from the margins, that seeks to build coalitions of solidarity based on difference.

About the contributor

Tarek Shukrallah (they/them) is an activist, educator, community organizer, writer and researcher based in Berlin. Tarek is a PhD student at the Doctoral School for Intersectionality Studies of the University of Bayreuth with a focus on intersectionality studies, queer studies, postcolonial studies, and queer of Color critique, and a lecturer at the Political Science Department of Philipps University Marburg. Tarek is active in political struggles against exploitation and oppression from a queer of Color perspective.